Music printing, a journey for engravers (part 1 of 3)

Lying in the sun on the deck with your MacBook Pro in one hand and a cool drink in the other... Need to get the parts for your latest masterpiece? No problem. Stay where you are, open the score up in Sibelius or Finale and view them. Want to change a chord? No problem. Alter it in the score and breathe a sigh of relief as your parts are automatically updated. Ready to print? No problem. Click, click, head inside to the printer to collect the score and parts. Easy. Yes, your heart is joyful, but it wasn't always like that! Recently I've been thinking about a few topics. Firstly, what exactly did it take for engravers to set and print music one hundred years ago, or even before that, and what has developed to lead us to where we are today. Secondly, what exactly is the distinction between music engravers and copyists and why is it so often confused. Thirdly, how are these roles and this information relevant to today? Let's start by looking at the journey engravers have taken over hundreds of years in order to set and print music.

This is the first of a three-part post. See also Music copying and confusion (part 2 of 3) and Changing times for music preparers (part 3 of 3).

In the Middle Ages very little was written, both in music and generally. The only music that was notated was sacred, as the church was such a huge force on society and they felt that having it written in music raised its meaning to a higher level. It was notated by hand on red lines with a calligraphy-type pen.

During the 15th Century, woodblock printing emerged. This is where you would level off a plane of wood and draw the music on in reverse. You would then carve the wood so that the symbols were elevated, ink it and then press it to paper. The consistency of this technique varied greatly, due to the soft and temperamental nature of wood and the often inaccurate process of inking the carved plate.

In the mid 15th Century the printing press was invented and was very quickly adapted to accommodate music and other mediums. Music symbols were now collated on a plate and then prepared for printing. This process was more reliable and allowed for easier reproduction, but the finer details of manuscripts were unable to be copied. These limitations meant that a new method needed to be developed - engraving.

Engraving was more time consuming but allowed for every fine detail to be notated. This method used a gradual process of etching and hammering into either zinc or copper. Again music would be set in reverse and in this method, unlike those previously, errors could be corrected easily by hammering the back of the metal.

In the late 18th Century in a bid to lower the cost of printing, lithography was invented. In this method oily ink was used to draw on the stone (or much later, a metal surface) and then acid was applied to burn the image to the stone. Water was then added, but repelled by the oil and therefore creating an environment for printing.

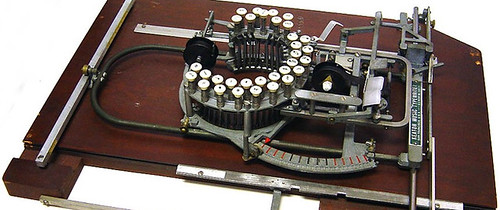

Music typewriters developed over a number of years but became popular in the late 19th Century. They were known for their relative user-friendly nature and so were popular with copyists and everyday musicians - unlike earlier methods suited more to dedicated engravers. They worked similarly to standard typewriters, just with music notes and symbols instead of letters, although some had extra keyboards and similar additions.

Then during the mid 20th Century computers and software started to emerge. There were various programs created and to various degrees of success. One was called "DARMS (Digital Alternate Representation of Musical Scores)", what a brilliant title.

Later in the 20th Century Sibelius, Finale and many other smaller and lightweight pieces of software were created. These programs, now hugely powerful, have not only massively changed how music can be published and produced, but how we write music in the first place. This undoubtedly is the greatest step forward in this journey we have taken.

Of course, perhaps most importantly, is handwritten music. After the Middle Ages and through all of the developments in technology mentioned above, handwritten music has continued to develop. From beginnings only at the highest sacred level, handwritten music gradually became more common throughout the classes, just as society became more literate. Music engravers doing it by hand had extreme skill, accuracy and a mighty attention to detail. Firm opaque paper was always used with black ink. Until music typewriters and later music software was invented, copyists solely performed their craft by hand.

This is the first of a three-part post. See Music copying and confusion (part 2 of 3) and Changing times for music preparers (part 3 of 3).